Taste Your Way Through Thailand: An Interview with Author Naomi Duguid

I’m not exactly sure how one becomes a “culinary anthropologist,” but I’m positive that it’s a title worth envying.

I’m not exactly sure how one becomes a “culinary anthropologist,” but I’m positive that it’s a title worth envying.

At least, Naomi Duguid, the traveller, writer, photographer, cook and author of more than half a dozen cookbooks, certainly makes it look that way.

Her book Hot Sour Salty Sweet dives into the cuisine of the countries that line the Mekong River. Read more below as she discusses with us the culinary offerings of Southeast Asia, the unique treat that is Thai tea and the best way to immerse yourself in Chiang Mai, her home away from home.

You’ve travelled extensively across Asia, from Myanmar to Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand, to name a few. Of all the places you’ve been, how did you decide on Chiang Mai as your “Asia-home” away from home?

Chiang Mai is such a cosmopolitan, liveable place. It’s not a huge city, but it’s large enough to be dynamic, it has a university, etc.

Unfortunately, I haven’t had the chance to spend much time there lately as I’ve been working on my new book, Taste of Persia, but I’m looking forward to returning after the tour to my apartment in Chiang Mai.

When you’re living/spending time in Chiang Mai – what are your beloved local spots? Your favourite place for an authentic meal?

My favourite place to eat is always at the market. I visit Talat Wararot, Chiang Mai’s oldest market a lot. Muang Mai Market is the main, big wholesale market that I love to take groups to, it’s fabulous and a must-see for anyone interested in food and cuisine.

Every Friday morning there’s a market called Talat Gin Haw. It’s very central and many people come to Chiang Mai from their homes in the mountains for this market – many Burmese people originally associated with Muslim traders from the north, as well as various other types of hill people.

Chiang Mai is an old trading town and is therefore at the crossroads of various interesting places. Talat Gin Haw epitomizes Chiang Mai’s connection to the Hindu land and the country further north. I always look forward to returning here and love all the sights and smells of this market.

What are some of your favourite local ingredients from the region?

Well, what I love most is the aromatics of all the herbs and spices. One of my favourites, kaffir lime leaves, or wild lime leaves as I call them, has such an incredible scent. Ingredients are typically combined so the smell of lime leaves and lemongrass really brings me back to Chiang Mai.

Galingale, a ginger relative, is another favourite of mine. It has a gorgeous taste when pounded or sliced into dishes and soups, which gives it a wonderful aroma.

Also – the smell of jasmine rice cooking is always one of the smells in the streets. And Thai coffee!

Tell us about Thai Coffee and how it differs from our traditional coffee.

Thai coffee is processed in a different way so it’s got a much more mocha taste with a little grain in it. It’s by far one of my favourite indulgences when I’m in Chiang Mai.

Street vendors make the coffee by putting it in a cloth bag and pouring boiling water through the bag into a pot. From here they’ll pour out the coffee and adjust its strength by thinning it with water or adding more ground coffee to the bag. Then it can be served with ice or condensed milk.

The interesting thing about Thai coffee is it really declined in popularity for many years, nearly disappearing altogether about 30 years ago when instant coffee was introduced and perceived as cooler.

From there, European coffee came in and pushed Thai coffee even further away. There were fewer and fewer stands but recently there’s been a bit of a resurgence and we’re able to find it now. Modernity, like so many other things, pushed it away for years.

What’s nice is that when it comes back you really get to appreciate it and the opportunity to find it. It reminds us that the things our grandparents knew about were so precious, and I’m thankful that with the way the cycle works, these things are able to come back around to be appreciated by people again.

In your book, Hot Sour Salty Sweet, you explore the cuisine in multiple countries along the Mekong River and recognize that the flavours and tastes from the surrounding countries were all closely related. How does Northern Thai cuisine differentiate itself from the rest?

In one region you can find the food of another, but they all have very distinct cuisines.

Northern Thailand has strong regional traditions and very intense flavours. There’s a pushiness and intensity of the flavours and spices that you don’t find in other regions.

In Northern Thai cuisine many things are steamed to cook and the grill is primarily used to flavour dishes. Chilies, garlic and shallots are all grilled first, then combined into a sauce or salsa, similarly to how it’s done in Mexico.

Since the grill is used to flavour, they grill over charcoal to create these lovely and intense sauces, like nam prik pao, for example.

Your latest cookbook on Persian cuisine focuses on a number of countries including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran and Kurdistan. Can you define this cuisine and how it differs from Thai cuisine?

The food in the Persian culinary region is representative of more temperament climate conditions. They use nuts more, to give meaning to food through the sauces.

There is much less fish in the culinary world of the Caucasus Mountains, and fruit plays a big role in the culinary flavours. In Thailand, the focus is more on bitter and aromatic leaves. In the Persian region, they use tart fruits and fresh herbs, because of the desert and drier climate in places like Southern Iran.

Similar to Thailand, rice is a big part of the cuisine. It differs in many ways though. In Thailand and most of Southeast Asia, jasmine rice is served as bread, used to balance out dishes and accompany the strong flavours of the main dish.

In Persian culinary tradition, basmati rice is important and flavoured while it cooks with salt and seasoning. They typically use flatbread as their plain dish to be served alongside strong flavours.

What’s your best advice for getting past the fear travellers sometimes have of eating in markets. It can be an overwhelming place, so how does one start?

There are typically a few reasons people struggle with eating in markets; the concern for cleanliness and the overwhelming variety of choices.

There are typically a few reasons people struggle with eating in markets; the concern for cleanliness and the overwhelming variety of choices.

Generally, in Thailand, there is a huge emphasis on cleanliness. There’s plenty of water in Thailand and the locals are known for showering to refresh themselves from the heat multiple times a day!

Many times I’ve entered friends’ homes and they ask if I’d like to refresh myself with a shower. It also helps to rest your body temperature.

This emphasis on cleanliness means that you don’t smell rotting fish in the markets, and the clean-up is so thorough that when they’re done for the day you can’t even tell there was a market there! This is especially impressive given the tropical climate.

Addressing the amount of choice, I’d recommend you don’t bother trying things you know you don’t like and don’t waste any eating opportunity on a western dish you could get back home. It’s important to try the local cuisine to help get an appreciation for the region and a true sense of the food landscape.

When travelling from Northern Vietnam to Southern Vietnam, the classic Vietnamese Pho dish changes along the way. What dishes change in a similar fashion from Myanmar into Chiang Mai? Is there a specific dish travellers should look for?

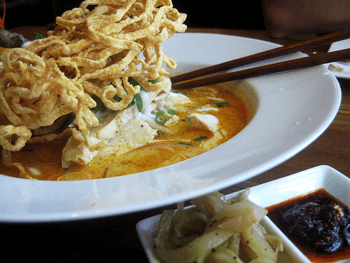

Khao soi (see recipe, below) is a dish widely served in Northern Thailand that is Burmese-influenced. It’s similar to Ohno khao swe, the Burmese noodle dish that is also a coconut milk-based dish.

Khao soi (see recipe, below) is a dish widely served in Northern Thailand that is Burmese-influenced. It’s similar to Ohno khao swe, the Burmese noodle dish that is also a coconut milk-based dish.

These dishes are very different but are related, as you can even see by their names. Also, generally, there is much less chilli heat used in Myanmar than in Northern Thailand so most dishes are different for that reason.

How do you think food helps one understand a place?

I’ve always seen the world through food, it’s the best window into a culture. I love taking groups into a region and focusing not on hands-on cooking but on seeing the world through food.

If you had one tip for travellers heading into the region, what would it be?

What’s most important is that you look at a topographic map to get an understanding of where you’re going.

Look at the mountains. Acknowledge where the Burma border lies. Observe where the Mekong winds.

In Chiang Mai, you’re at a meeting place of cultures, where the lowlands meet the mountains. From town, you can see the hills, and it’s remarkable to think that Myanmar is just across the mountains.

It may seem close, but back in the day, those were very hard to cross. When you travel by plane sometimes you forget where you are and how you got there.

Understanding by taking the time to look at a map beforehand will leave you with a real appreciation for the region and a sense of wonder to see where you are in relation to the rest of Southeast Asia.

Editor’s Note: Naomi was kind enough to share the below recipe and excerpt from her book, Hot Sour Salty Sweet, coauthored with Jeffrey Alford.

Recipe: Chiang Mai Curry Noodles

We’re told by friends in Chiang Mai, Thailand’s northern capital, that this noodle dish is originally from the Shan State of Burma; others say it came with Muslim traders from Yunnan.

Whatever the story, khao soi is now known as a Chiang Mai specialty. It’s an easy-to-make, very rich and delicious one-dish meal.

The broth that bathes the noodles is flavoured with a little curry paste, turmeric, and garlic and is smooth and thick with coconut milk. Traditionally khao soi is made, as it is here, with beef; you can also make it with chicken.

The recipe calls for Chinese egg noodles, available from most Chinese groceries. They come in one-pound packages and are about linguine width and pale yellow. The cooked noodles are placed in large individual bowls and the curry sauce is poured over them when the dish is served.

Khao soi is usually topped with a small nest of crispy noodles, egg noodles that have been briefly deep-fried; they add a delightful contrasting texture. There is a small array of condiments traditionally served with khao soi; don’t worry if you don’t have pickled cabbage.

Khao soi – Northern Thailand

Serves 4

Ingredients:

2 to 3 cloves garlic, peeled

1-inch piece fresh turmeric, minced, or 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

1 teaspoon salt, plus a pinch

1 tablespoon Red Curry Paste (page 210 or store-bought)

1 tablespoon peanut or vegetable oil

3 cups canned or fresh coconut milk, with 2 cup of the thickest milk set aside

2 pound boneless flavorful beef (sirloin tip or trimmed stewing beef), cut into 2-inch chunks

1 tablespoon sugar

1 cup water

3 tablespoons Thai fish sauce

1 tablespoon fresh lime juice

Peanut oil for deep-frying noodles (optional)

1 pound Chinese egg noodles (bamee)

Toppings & Condiments

Fried noodle nests (optional; see below)

2 cup coarsely chopped shallots

2 cup minced scallions

2 cup Pickled Cabbage, Thai Style

1 lime, cut into wedges

Directions:

Place the garlic in a mortar with the turmeric and the pinch of salt and pound to a paste. Alternatively, finely mince the garlic and whole turmeric, if using, and place the garlic and turmeric in a small bowl with a pinch of salt.

Stir in the red curry paste and set aside.

Place a large heavy pot or wok over high heat.

Add the 1 tablespoon oil and, when it is hot, toss in the curry paste mixture.

Stir-fry for 3 seconds, then add the reserved 1/2 cup thick coconut milk and lower the heat to medium-high.

Add the meat and sugar and cook, stirring frequently, for 4 to 5 minutes, until the meat has

changed colour all over.

Add the remaining 1/2 cups coconut milk, the water, fish sauce, and the remaining 1 teaspoon salt and bring to a boil, then reduce the heat to medium and cook at a strong simmer

for about 10 minutes.

Remove from the heat and stir in the lime juice. (The soup can be prepared up to an hour ahead, then reheated just before serving.)

Meanwhile, make the optional crispy noodles:

Place a plate lined with several layers of paper towels by your stove. Place a large wok or heavy pot over high heat and add about 1 cup peanut oil.

When the oil is hot, drop in a strand of uncooked noodles to test the temperature. It should sizzle slightly as it falls to the bottom, then immediately puff and rise to the surface; adjust the heat slightly, if necessary.

Toss a handful (about 1 cup) of noodles into the oil and watch as they puff up. Use a spatula or long tongs to turn them over and expose all of them to the hot oil. They will crisp up very quickly, in less than 1 minute.

Lift the crisped noodles out of the oil and place on the paper towel-lined plate. Give the oil a moment to come back to temperature, and then repeat with a second handful of noodles. (The noodles can be fried ahead and left standing for several hours.)

To serve, bring a large pot of water to a vigorous boil over high heat. Drop in the remaining noodles (or all noodles, if you didn’t make crispy noodles), bring back to a boil, and cook until tender but not mushy, about 6 minutes. Drain well.

Divide the drained noodles among four large bowls. Ladle over the broth and meat. Top with crispy noodles, if you have them, and a pinch each of shallots and scallions.

Serve with the remaining condiments set out in small bowls so guests can garnish their soup as they wish. Provide each guest with chopsticks and a large spoon.

Excerpted from Hot Sour Salty Sweet by Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid. Copyright © 2000 Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid. Excerpted with permission from Random House Canada, an imprint of RH Canadian Publishing., a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Limited. All Rights Reserved.

MORE FROM Asia-Pacific + Thailand

Biking in Cambodia with B&R Expert Guide Fin

Cambodia

The Slow Fund: Rice Production with Ozuchi Village

Japan

Take a Virtual Ride on the Hai Van Pass in Vietnam

Vietnam

How Three Cambodian Hotels Are Joining Forces to Feed Their Communities

Cambodia

Meet Fin—B&R’s Expert Guide in Cambodia

Cambodia

An Insider’s Eye on Vietnam: What to See and What to Skip, According to our Vietnam Expert

Vietnam

Photo Essay: Exulting in Mongolia’s Eternal Blue Sky

Mongolia

The Best Times of Year to Travel to Asia

Vietnam

Chris Litt: On Mongolia and the Desire to Disconnect

Mongolia

Top 6 Multi-Day Walks in Australia

Australia

The 8 Best Restaurants in Auckland

New Zealand

The 5 Best Restaurants in Wellington

New Zealand

8 Reasons Why You Need to Take an Australian Adventure

Australia

Cultural Quirks About Bhutan That Will Blow Your Mind

Bhutan

5 Things to Know Before You Go to Japan

Japan

8 Favourite Restaurants to Eat in Queenstown

New Zealand

10 Must-Try Australian Wines

Australia

Where to Eat in Hong Kong: 7 Best Restaurants

China

A Kiwi’s Guide to Enjoying New Zealand

New Zealand