In Deep: The Wild Coast of British Columbia

Born and raised in British Columbia, it’s second nature for me to sing the numerous praises of my home province. Most visitors know a little bit about the two major cities of the province—Vancouver, the home of the 2010 Winter Olympics, or even the British vibe of its capital city, Victoria, situated on Vancouver Island, but even fewer people know about some of its most beautiful places, along its north-central coast.

In our busy world, it can be deeply welcoming, renewing, and inspiring to leave ‘civilization’ and the daily grind behind in order to step back into nature, take a deep breath (or three), and reconnect to the world of flora and fauna around us—perhaps reverting to the carefree time of childhood. And for those of us who are raising children or travelling with them, there is really nothing like bringing younger generations to these increasingly harder-to-find unspoiled places in the world. Here’s the British Columbia I know from my youth, and from my years of extensive travelling and exploring; it’s one worth getting to know. From marine parks to untouched rainforest, B.C. is the most biodiverse place in Canada

In our busy world, it can be deeply welcoming, renewing, and inspiring to leave ‘civilization’ and the daily grind behind in order to step back into nature, take a deep breath (or three), and reconnect to the world of flora and fauna around us—perhaps reverting to the carefree time of childhood. And for those of us who are raising children or travelling with them, there is really nothing like bringing younger generations to these increasingly harder-to-find unspoiled places in the world. Here’s the British Columbia I know from my youth, and from my years of extensive travelling and exploring; it’s one worth getting to know. From marine parks to untouched rainforest, B.C. is the most biodiverse place in Canada

Broughton Archipelago Provincial Park

Welcome to B.C.’s largest marine park, established in 1992, located on the north side of the Queen Charlotte Strait. These traditional grounds were first utilized by First Nations peoples (the Kwakiutl) for generations, with its islands, islets and sheltered waters a rich place for the gathering of food, and the building of villages and settlements.

Welcome to B.C.’s largest marine park, established in 1992, located on the north side of the Queen Charlotte Strait. These traditional grounds were first utilized by First Nations peoples (the Kwakiutl) for generations, with its islands, islets and sheltered waters a rich place for the gathering of food, and the building of villages and settlements.

If you look closely around while walking inland, you may see cedars hundreds of years old, which are also known as culturally modified trees, as you can see remnants of sustainable forestry practiced by the First Nations. Or perhaps you’ll see the park’s lone petroglyph, carved into a rock on the north side of Berry Island by the original people who inhabited these lands. The biggest islands here are named: Broughton Island, North Broughton Island, Eden Island, Bonwick Island and Baker Island.

If you look closely around while walking inland, you may see cedars hundreds of years old, which are also known as culturally modified trees, as you can see remnants of sustainable forestry practiced by the First Nations. Or perhaps you’ll see the park’s lone petroglyph, carved into a rock on the north side of Berry Island by the original people who inhabited these lands. The biggest islands here are named: Broughton Island, North Broughton Island, Eden Island, Bonwick Island and Baker Island.

With this isolated region accessible only by boat, it’s become popular with sea kayakers looking to encounter the wildlife along the coast. From the famous orca, seasonal sightings of humpback whales, to harbour seals and harbour porpoises, sea lions (who have a number of haul-outs within the boundaries of the park, giving you an incredible view of their hilarious social lives as they sun and rest on the rocks!) and sea otters. Looking up, you may see bald eagles, along with seabirds such as cormorants, Great Blue herons and Harlequin ducks.

A Note on the Orca

Not a whale at all, but actually the largest dolphin species, this distinctive black-and-white aquatic mammal, Orca orcinus, also known as the killer whale. This resident species is familiar to any B.C. resident along the shoreline, with 75 local whales who spend the summers along the waters of British Columbia and Washington State and wander as far as southeast Alaska to central California. This group of orcas are the most studied population of orcas in the world, and the only population listed as endangered.

Not a whale at all, but actually the largest dolphin species, this distinctive black-and-white aquatic mammal, Orca orcinus, also known as the killer whale. This resident species is familiar to any B.C. resident along the shoreline, with 75 local whales who spend the summers along the waters of British Columbia and Washington State and wander as far as southeast Alaska to central California. This group of orcas are the most studied population of orcas in the world, and the only population listed as endangered.

These predators are found in each one of the world’s oceans, from tropical seas to the Arctic and Antarctic regions. (The only waters where you won’t find them are in the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and parts of the Arctic Ocean). They are extremely social, with a complex society; only elephants and higher primates (including humans) live in comparably nuanced social groups. I have seen some incredible things on my trips, including a very rare humpback whale and orca battle (in which the humpback emerged victorious, saving her calf from an orca who was trying to hunt her baby).

Orcas band in matrilineal family groups, pods, where they pass down their own sophisticated vocalizations, hunting techniques, and other behaviours down through generations, often specific to their own family group only. With a huge diversity in their diet, they hunt in groups like wolf packs and will go for fish, mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, or even sharks and rays, depending on what part of the world they live in. The Some pods have distinctive diets that vary by their location, having an obvious impact on their prey species; on average a killer whale will eat 227 kilograms (500 pounds) of food per day.

Orcas band in matrilineal family groups, pods, where they pass down their own sophisticated vocalizations, hunting techniques, and other behaviours down through generations, often specific to their own family group only. With a huge diversity in their diet, they hunt in groups like wolf packs and will go for fish, mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, or even sharks and rays, depending on what part of the world they live in. The Some pods have distinctive diets that vary by their location, having an obvious impact on their prey species; on average a killer whale will eat 227 kilograms (500 pounds) of food per day.

Bella Coola and the Nuxalk People

Located in the Bella Coola Valley, this small town of the same name has a population of just a little over 2,000 people, and is a known spot for heli-skiing. The traditional home to the Nuxalk people, who have existed here long before any formal written history, you will find a series of fantastic petroglyphs at Thorsen Creek, carved directly into the rocks. These images of beautifully rendered animal and supernatural beings date between 5,000 and 10,000 years old.

The Nuxalk are an Indigenous First Nation in Canada, who numbered about 35,000 people pre-European contact; in 1862, the smallpox epidemic (introduced by European settlers to British Columbia) reduced the Nuxalk to a population of 300 survivors; today, it is estimated there is a total Nuxalk population of approximately 1,400, with about 900 people living on the nearby Nuxalk reserve near Bella Coola. It is worth noting that the Nuxalk Nation have never ceded, sold, surrendered, nor lost their traditional lands through act of war or by treaty. Also worth noting in the Bella Coola Valley is the abundance and critical habitat for bears, which leads us to….

The Nuxalk are an Indigenous First Nation in Canada, who numbered about 35,000 people pre-European contact; in 1862, the smallpox epidemic (introduced by European settlers to British Columbia) reduced the Nuxalk to a population of 300 survivors; today, it is estimated there is a total Nuxalk population of approximately 1,400, with about 900 people living on the nearby Nuxalk reserve near Bella Coola. It is worth noting that the Nuxalk Nation have never ceded, sold, surrendered, nor lost their traditional lands through act of war or by treaty. Also worth noting in the Bella Coola Valley is the abundance and critical habitat for bears, which leads us to….

Go West With The Whole Family

The ultimate family vacation, make your way to the wild coast of British Columbia on our Bears and Whales Family Adventure. Tune into nature on an epic coastal quest in search of orcas, porpoise, dolphin and seal, moving inland to ancient cedar groves on the lookout for grizzly bears on the move.

DETAILED ITINERARYThe Great Bear Rainforest

One of the world’s most pristine environments, the Great Bear Rainforest is named for its namesake, the rare and elusive Kermode (or spirit) bear, as well as for its old-growth temperate rainforest. This is the only place on earth to find this subspecies of the American black bear. Due to a recessive gene, about one in ten black bear cubs are coloured white. The spirit bear holds a sacred role in the oral traditions of the indigenous peoples in the region. It is estimated that there are between 100-500 fully white-hued bears in the rainforest. The prime bear-viewing season is in late August through September/October, as salmon spawning season begins, and the bears begin to gather themselves for a salmon-eating feast, however, springtime provides visitors an opportunity to see bear cubs alongside their mothers, taking in their first experiences of life.

One of the world’s most pristine environments, the Great Bear Rainforest is named for its namesake, the rare and elusive Kermode (or spirit) bear, as well as for its old-growth temperate rainforest. This is the only place on earth to find this subspecies of the American black bear. Due to a recessive gene, about one in ten black bear cubs are coloured white. The spirit bear holds a sacred role in the oral traditions of the indigenous peoples in the region. It is estimated that there are between 100-500 fully white-hued bears in the rainforest. The prime bear-viewing season is in late August through September/October, as salmon spawning season begins, and the bears begin to gather themselves for a salmon-eating feast, however, springtime provides visitors an opportunity to see bear cubs alongside their mothers, taking in their first experiences of life.

This 6.4 million hectare rainforest (about the size of Ireland!) occupies 400 kilometres (250 miles) of coastline along the central and northern coast of British Columbia. It is one of the last unspoiled temperate rainforests left in the world and is accessible only by boat or floatplane. Notable trees here include thousand-year-old western red cedars, whose foliage is strongly aromatic, having the scent of pineapple when crushed; you’ll also find the tallest species of spruce, the Sitka spruce, which grow as tall as 90 metres (295 feet). The government of British Columbia agreed in 2016 to permanently protect 85% of the old-growth forests from industrial logging. This historic multilateral negotiation was finally agreed upon after about 25 years of talks between tourism, logging companies, mining companies, and First Nations peoples, a worldwide achievement in how to manage and conserve forests in a positive way for the greater good. It’s also worth mentioning that grizzly bear trophy hunting is banned, not only in the Great Bear Rainforest but in all of British Columbia, a monumental feat that was passed only in 2017, after many years of debate. On a positive note, it is clear that bear-watching tourism in the Great Bear Rainforest is bringing in twenty times the income of hunting for the region.

The Great Bear Rainforest was visited by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2016, and is also officially endorsed by the royal family as part of The Queen’s Commonwealth Canopy Initiative. Bordering the green forests inland, the coastal landscape is home to a number of aquatic and semiaquatic species, including playful sea otters, dolphins, sea lions, and whales.

Tweedsmuir Provincial Park

Originally one park established in 1938 as a result of a visit by John Buchan, Lord Tweedsmuir (and then Governor-General of Canada, the Queen’s representative in the country), who had a chance to take a float plane above the brilliant Rainbow Range of mountains, and ride by horseback in this wilderness, Tweedsmuir Provincial Park has since been cleaved into two separate parks: Tweedsmuir South Provincial Park, and Tweedsmuir North Provincial Park and Protected Area. The total area of both parks combined is 989,000 hectares in size. Tweedsmuir South is another hot spot and nature corridor for prime grizzly bear viewing, especially in the Atnarko and Bella Coola Valleys; there is a bear-viewing platform located within the park allowing for safe viewing, protecting both bears and humans and minimizing any unnecessary contact.

Originally one park established in 1938 as a result of a visit by John Buchan, Lord Tweedsmuir (and then Governor-General of Canada, the Queen’s representative in the country), who had a chance to take a float plane above the brilliant Rainbow Range of mountains, and ride by horseback in this wilderness, Tweedsmuir Provincial Park has since been cleaved into two separate parks: Tweedsmuir South Provincial Park, and Tweedsmuir North Provincial Park and Protected Area. The total area of both parks combined is 989,000 hectares in size. Tweedsmuir South is another hot spot and nature corridor for prime grizzly bear viewing, especially in the Atnarko and Bella Coola Valleys; there is a bear-viewing platform located within the park allowing for safe viewing, protecting both bears and humans and minimizing any unnecessary contact.

Additional features located within Tweedsmuir South include the shield volcanoes, especially the fantastic Rainbow Range of mountains, ribboned with multiple colours from heavy mineralization volcanic lavas and sands. Hunlen Falls, one of Canada’s tallest unbroken waterfalls, dropping 260 metres (853 feet), is located within the park, accessible via float plane or a 16-kilometre (10-mile) hike. It was named in 1947 for the name of a Chilcotin Chief named Hana-lin, who used to fish and hunt in the spot beneath the falls. Other notable features in the park include the site of Lonesome Lake, an s-shaped lake visible from Hunlen Falls; along its south end, the homesteader-cum-conservationist Ralph Edwards lived there from 1912 until the 1970s, advocating for the protection of the trumpeter swan and wildlife in general.

The Nuxalk-Carrier Route: A System of Trade and Transport

Also known as the Blackwater Trail or the Alexander MacKenzie Heritage Trail, this 420-kilometre-long (260-mile) trail is a historical overland route used by the First Nations of the Nuxalk and Carrier people. It traces a path between Quesnel and Bella Coola, one of the many grease trails, communication and trade routes that connected the Pacific coast to inland communities. These grease trails, of which this particular route is known as the Grease Trail, allowed for the trade of oolichan oil, the processed oil of the eulachon fish (which was used as a condiment similar to butter to supplement first peoples’ diets inland). Other items traded commonly included furs, obsidian, copper, and other items of importance. A relay system in which items were traded originally covered a vast area from the present-day Yukon Territory in Canada to northern California, and as far east as central Montana and Alberta, Canada.

In the late 18th century, the Scottish explorer Alexander MacKenzie who accomplished the first east-to-west crossing of North America north of Mexico, made his way to the Pacific Ocean along this trail, led by Nuxalk-Carrier guides, when his westerly route along the Fraser River was prevented by obstacles. He travelled through what is now Tweedsmuir Provincial Park, over the Rainbow Mountains and into the Bella Coola Valley on his trek. Any modern-day explorers hoping to take on this trail should know the route is long and difficult, so experienced hikers can expect to finish it in about 18 days; intermediate hikers could require at least 24 days.

Either way, whether you are hiking the extended trail, or even taking the shortest of walks along the path—and indeed, anywhere you travel in this part of B.C., you are sure to feel something special all around you, as we learn about the cultures and generations who have walked the earth before us, and as we aim to preserve and share these unique places with generations to come.

MORE FROM North America + Canada

Discover Canada’s East Coast From Home

Canada

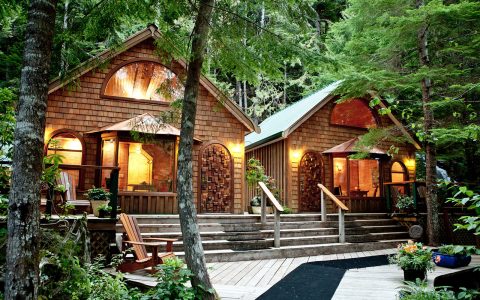

The Pacific Yellowfin Hotel Review

Canada

Reflections & Impressions: Dane Tredway’s trip to the Arctic

Canada

The 2019 Masters: Hearing ‘The Tiger Roar’ Firsthand

United States

After the Eruption: Why There’s Never Been a Better Time to See Hawaii

United States

The 13 Best Places to Eat in Quebec City

Canada

The 11 Top Restaurants in Vancouver

Canada

5 Over-the-Top Alaskan Luxury Lodges We Love

Alaska

Most Over-The-Top Spots to Snap the Rockies

Canada

24 Hours in St. John’s, Newfoundland

Canada

Our Coolest Hot Spot For Winter: Quebec City

Canada