Insider's Guide:

Budapest Baths

As a proud Hungarian, I always insist that visitors to my home city take up the opportunity to soak up some local culture by visiting our world-famous baths. Taking to the hot springs is every Hungarian’s preferred way to relax and heal—perfect after a long travel day, or, a final chance to de-stress before embarking on your journey back home. Here are my tips to help you make the most of Budapest’s watery world.

Centuries of Bathing Culture

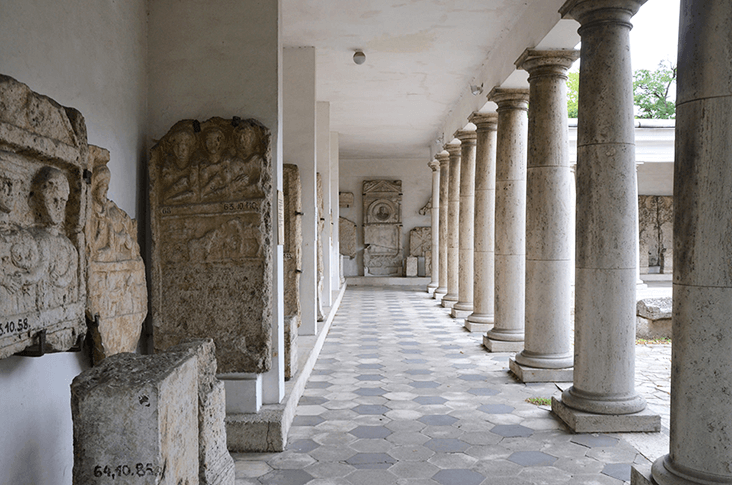

The bathing culture here in Budapest is as old as the city itself—more than 2,000 years old. The collision of tectonic plates in the area caused hundreds of hot springs to bubble up along the Buda side of the Danube. Mineral hot springs with healing qualities have long been a draw for those settling here. The Romans initially called this place Aquincum, aqua for water; other scholars suggest the name “Buda” comes from the Slavic word voda for water.

Over the centuries, each culture inhabiting this region utilized this miraculous resource according to their customs; as a result, there is a very old and diverse tradition of how to bathe.

Old School: Turkish hammams

Today, there are basically two main schools of baths in Budapest. The first is the original Turkish bath. During the Turkish occupation in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Turks established bathhouses in Buda following their customs back home. It’s important to note that back in Turkey, there was hardly any geothermal water; therefore, a traditional Turkish hammam, or bathhouse, generally features the signature service of a body scrub on a marble table.

Today, there are basically two main schools of baths in Budapest. The first is the original Turkish bath. During the Turkish occupation in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Turks established bathhouses in Buda following their customs back home. It’s important to note that back in Turkey, there was hardly any geothermal water; therefore, a traditional Turkish hammam, or bathhouse, generally features the signature service of a body scrub on a marble table.

Here in Budapest, you will see that the Turks constructed similar architectural features at the hammams here, but instead of massage tables, the wise decision was made to construct pools inside their baths, taking full advantage of the springs.

The unique thing about the Turkish baths, apart from the fact that the basic structures are almost 500 years old, is that they contain the essence of Eastern philosophy. Each pool is a different temperature and there is a certain order one must go through. As you gradually increase your body temperature in the circuit, moving into warmer pools, and eventually switching between hot and cold pools, it creates a sense of mental preparation and, ideally, puts you in a meditative state. (Your results are more tangible, too: your skin will be nice and smooth, and your circulation is increased, giving it a healthy tone).

Bathe like a pro at the Rudas Turkish Baths

The most famous Turkish bath in Budapest is the Rudas Bath, initially built in 1566. A popular bath for tourists (and locals alike), I often notice newcomers lingering around, seemingly uncertain about what to do or how to use the pools. Here’s a circuit that I like to follow in this particular bath that will help you understand how to use it best.

The most famous Turkish bath in Budapest is the Rudas Bath, initially built in 1566. A popular bath for tourists (and locals alike), I often notice newcomers lingering around, seemingly uncertain about what to do or how to use the pools. Here’s a circuit that I like to follow in this particular bath that will help you understand how to use it best.

Scheduled River Cruise Group Biking Trip

Four countries, three world capitals, and a slew of historic medieval strongholds, modern art museums and towering castle ruins along the way—oh, and did we mention wine country? On our Danube River Cruise Biking trip, see the best of Mitteleuropa.

DETAILED ITINERARYStart at the sauna and turn up the heat

Your preparation starts in the sauna, which is on the right-hand side when you enter the main pool area. The sauna helps to acclimatize your body to the next step…making a circuit of the pools, gradually increasing your body’s temperature through each step.

Your preparation starts in the sauna, which is on the right-hand side when you enter the main pool area. The sauna helps to acclimatize your body to the next step…making a circuit of the pools, gradually increasing your body’s temperature through each step.

Post-sauna, I will make a circuit through the pools one by one, starting with the coldest, which is 28 degrees Celsius (82° F). The idea behind this circuit is that you gradually heat your body temperature up; when you start to feel a little bit chilly, make your way over to the next pool to warm up.

There are five pools in the main pool area. Starting at the bottom right-hand corner, the first pool is at 28°C (82°F); the bottom left pool is 30°C (86°F); the pool at the top left corner is heated to 33°C (91.4°F); the big pool in the middle is 36°C (96°F); then the pool at the top right corner is heated to 42°C (107.6°F). Of course, the 42°C pool would be much too hot for your body unless you first make your way through the preceding pools.

When you graduate to the 42°C pool, stay just a few minutes in it, then head to the cold plunge pool around the corner that is kept to 12°C (53°F). After a plunge of 30 seconds to one minute (or more, if you can stand it!), hop back into the 42-degree pool. Repeat the hot-cold circuit three to four times; this is the pinnacle of your bath experience.

Now comes the relaxing phase. After my last visit to the 42-degree pool, I usually go back to the 28-degree pool to cool down a bit, then I head to the steam room, and finally to the 30-degree pool for a final soak; I take a post-circuit shower before I leave. The entire process takes about two to two-and-a-half hours, and it is very exhausting for the body. For this reason, after having your final shower, you are supposed to take a quick nap of at least 20 minutes in the nap room, which is located just outside of the pool area.

A few practicalities about the Rudas baths: during the week, it is men only, except for Tuesday, which is a women’s-only day. During the week, you do not have to wear a bathing suit; a few people also wear only the loincloth that is provided to you upon entrance. On weekends, the baths are coed.

Other Turkish Baths in Town

The only other original Turkish bath that survived is the Király Bath. However, it has not been maintained as well as the Rudas Baths, and the temperature of the pools is different; here, the hottest pool is heated to 40°C (104°F); it is coed all through the week.

The only other original Turkish bath that survived is the Király Bath. However, it has not been maintained as well as the Rudas Baths, and the temperature of the pools is different; here, the hottest pool is heated to 40°C (104°F); it is coed all through the week.

Veli Bej is a new, modern Turkish bath, very nicely done. It is not an original bath from the Turkish period, but it is designed in a similar fashion, following the examples of the others. Apart from the typical structure of the pools, it has modern facilities as well. It is coed all through the week.

Palatial Pools from the 19th c.

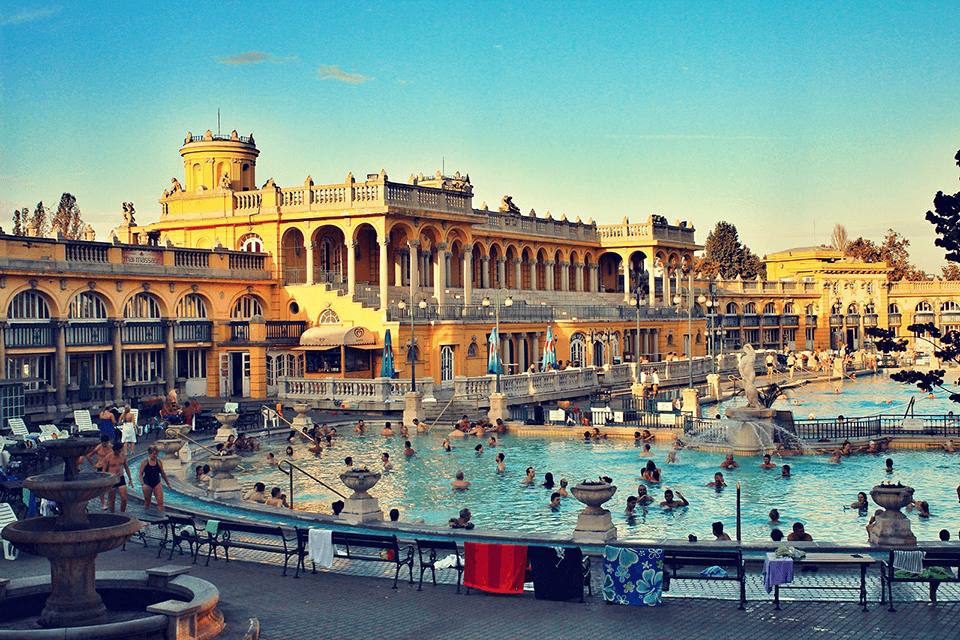

The other major school of baths in Budapest originates from the end of the 19th century. This is the time when the nation started to industrialize and, as a result, an emergent middle class appeared by the end of the century. To satisfy the needs of this class, a new bathing culture started to develop. As opposed to the baths built during Turkish times, which served hygienic purposes and involved a certain philosophy, the key driving force behind these new baths was simply that of grandeur and beauty. Here, there is no set ‘way’ to do the baths; you’re sitting in a tub or various pools for hours without a goal, other than socializing and hanging out as the bourgeoisie did!

As such, these baths are designed to look like lavish palaces with beautiful pools inside. The most typical example of these baths is the Széchenyi Bath. It is one of the biggest bathing complexes in Europe with 18 pools, both indoor and outdoor. This labyrinthine setup is easy to get lost in, but wonderful for its variety and its social atmosphere!

Another fine example of these palatial baths is the one at the Hotel Gellert, which has a slightly different history. Constructed for the elite, the high-class Art Nouveau grand hotel was finished only in 1918; a few months later the monarchy fell apart, along with it the social structure that supported the one-percenters.

Soon later, in the 1930s, after society restabilized and the economy recovered somewhat, Hotel Gellert reached its ‘golden age’, once more attracting the moneyed middle class. At the time, it was considered to be the most modern hotel in Hungary; the bath section featured a pool with artificial waves, which created quite a stir in a landlocked country.

During the Second World War, the Gellert was severely damaged; during the Socialist era, it became nationalized. And so, one of the most popular ‘elite’ meeting places was finally opened to the masses; one of the features of so-called “Gulyás Communism”, that although people could not freely travel, at least they had access to these facilities that were once out of reach for the average citizen.

Over the years, the grand hotel got more and more worn down; the tiles in the bath started to fall off; in the restaurant, its once-refined gourmet specialties were replaced by the proletarian duo of sausages and beer. (If you have seen Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, its façade is inspired in part by the Gellert…one could also say the tarnished glory of the Gellert is also echoed in the film itself.)

MORE FROM + Hungary

9 Must-Sees Along the Danube River

Austria

Vines 102: Hungarian Wines to Savour

Hungary

Vines 101: An Introduction to Hungarian Wine

Hungary

Butterfield & Robinson Danube Biking Cruise

Austria

Butterfield & Robinson Introduces Biking River Cruise

Austria

River Cruises Get Active

Austria